What causes workplace sexual harassment?

Workplace sexual harassment is caused by power imbalances. In Australian workplaces, the main power imbalance is gender inequality.

To prevent sexual harassment in the workplace, it's important to understand the key underlying drivers of sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is a social problem. Stopping it is not just about altering the behaviour of individuals; we need to change the culture and environment of workplaces in which it occurs. To prevent sexual harassment from happening in the first place, we must recognise the systemic and contextual issues that drive these behaviours. Primary prevention is all about addressing the root causes (or drivers) of sexual harassment.

Power relates to the possession of control, authority, or influence over others; it has many dimensions. The concept of power, and specifically, the misuse of power, is central to understanding the causes of sexual harassment.

In the workplace, power dynamics are commonly thought to be associated with an individuals’ seniority, age or value to a business. For instance, a harasser might be in a position of power due to being the owner of a business, a valued customer of a business, a direct supervisor of a person harassed, or in a position to influence that person’s future career prospects.

Gender inequality is a key driver, or underlying cause, of workplace sexual harassment. Other forms of discrimination and disadvantage create power imbalances in the workplace which can intensify an individual’s experience of sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment is recognised at an international level as a form of violence against women, with many of the same underlying drivers as other forms of violence against women. Gender inequality occurs when power, opportunities and resources are not shared equally between men and women in society and when women are not valued and respected as much as men.

Gender inequality

The unequal distribution of power, resources, opportunity, and value afforded to men and women in a society due to prevailing gendered norms and structures.

Gender inequality is also created by attitudes, norms and behaviours that suggest that heterosexuality is the normal or preferred sexual orientation and that people’s preferred gender identity is the one they are born with (cisgender). These norms, attitudes and behaviours have an impact on how people understand binary gender roles and gendered norms in society. There are other aspects of the social context that are also relevant to an understanding of violence against women.

Gender inequality cannot be disentangled from other social injustices because gendered inequality frequently intersects with other forms of structural and systemic discrimination, inequality and injustice. This means that the value afforded to women and men is not afforded in the same way for all women or all men, and that our society, institutions and organisations are shaped by those intersections. These intersections also influence the prevalence, dynamics and impacts of violence against women.

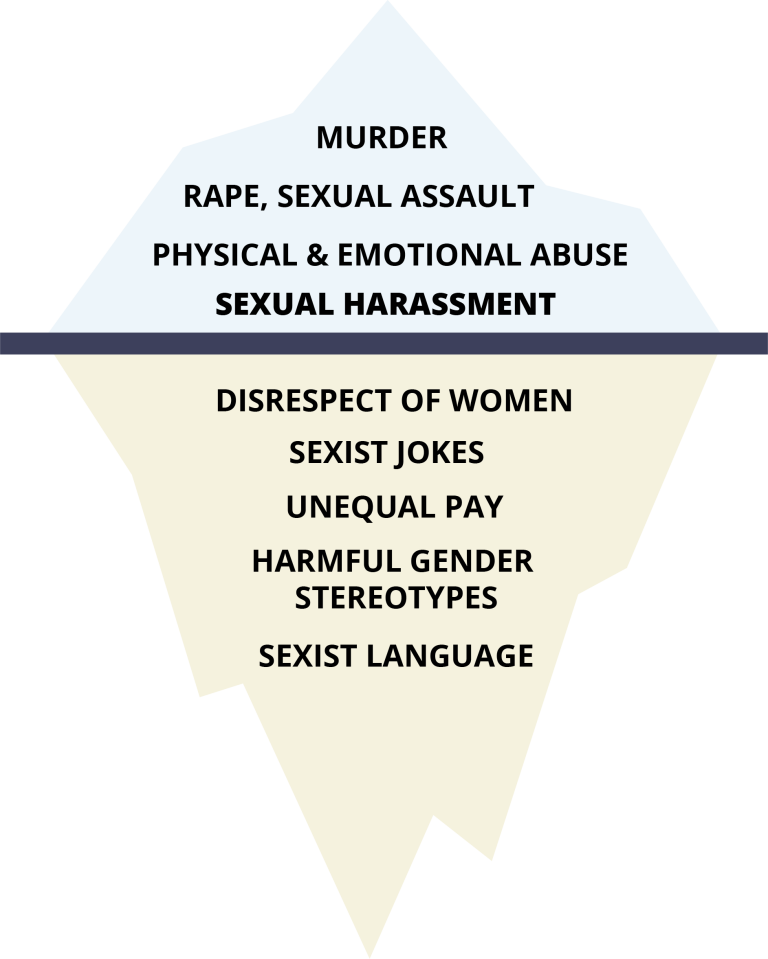

Consider the graphic below - gender inequality lies below the surface driving sexual harassment.

Understanding sexual harassment as driven by gender inequality also recognises that men and people with diverse gender identities and expressions also experience and are affected by sexual harassment. The 2018 National Survey clearly showed that sexual harassment is an issue for men as well as women. However, women were more likely than men to have been sexually harassed in the workplace in the previous five years (39% of women compared with 26% of men). When looking at victims of sexual harassment overall, women made up almost three in five (58%) of victims of workplace sexual harassment in the past five years. The survey confirmed all previous research in finding that the majority of workplace sexual harassment is perpetrated by men. 79% of victims of workplace sexual harassment were sexually harassed by one or more male perpetrators.

Sexual harassment experienced in the workplace

(2018 National Survey)

of women

of men

A key factor that drives sexual harassment of all people, regardless of their gender, are norms, practices and structures in society that shape (and are shaped by) gender inequality.

Gendered norms: the most common and dominant ideas, values or beliefs about gender in a society or community. This includes ideas about what is ‘normal’ in relation to gender, and beliefs about what people should do and how they should act—for example, the belief that mothers should be the primary carers of children, and the expectation that ‘boys don’t cry’.

Gendered practices: the everyday practices and behaviours that reinforce and maintain gendered norms—for example, parents telling boys to ‘toughen up’, or the over-representation of women in the childcare sector.

Gendered structures: the laws and systems that organise and reinforce an unequal distribution of economic, social and political power, resources and opportunities between men and women—for example, lower pay rates in female-dominated sectors such as child care.

Change the Story is an initiative from Our Watch that provides an evidence based framework for preventing violence against women. This can be used as a basis for understanding the drivers of sexual harassment and for taking action to address it.

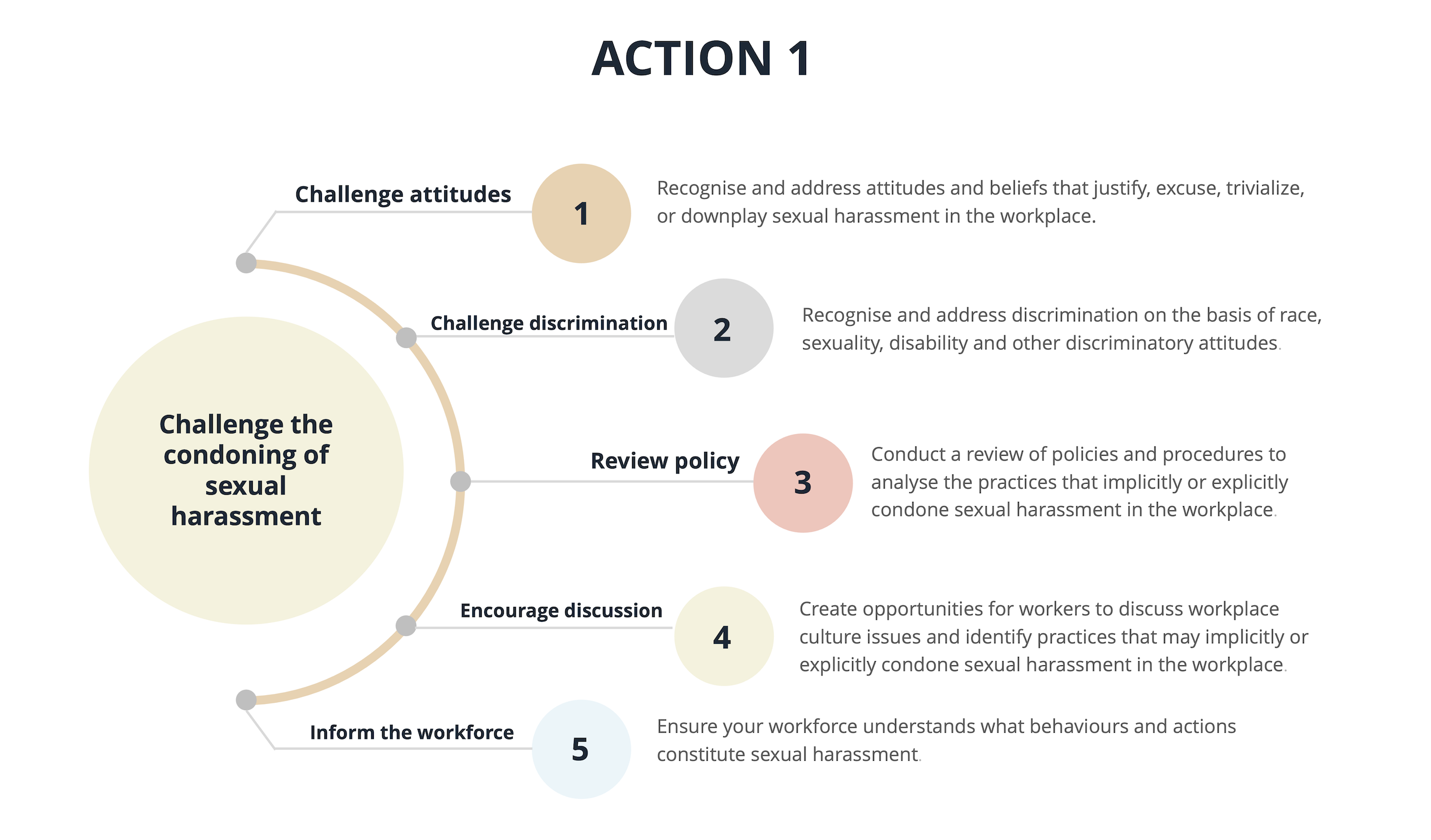

Driver 1: Condoning of sexual harassment against women

When workplaces support or condone sexual harassment against women, levels of sexual harassment are higher. Change the Story notes that violence against women is condoned through social norms and structures that justify, excuse or trivialise the behaviour, or shift the blame from the harasser to the victim. Change the Story points out that this should be understood as the direct consequence of other expressions of gender inequality. Workplace sexual harassment can sometimes be justified or excused on the basis that it was acceptable for men to behave in this way, or that the harassers were ‘from a different generation’, and so ‘don’t know any better’. Sexual harassment may also be trivialised by denying the behaviour was sexual harassment or that it had occurred, or by downplaying its seriousness.

Blame can be shifted to the victim of the workplace sexual harassment, which sends a strong and clear message that the workplace condoned the behaviour.

Click on the link below to consider what actions you can take to address driver 1.

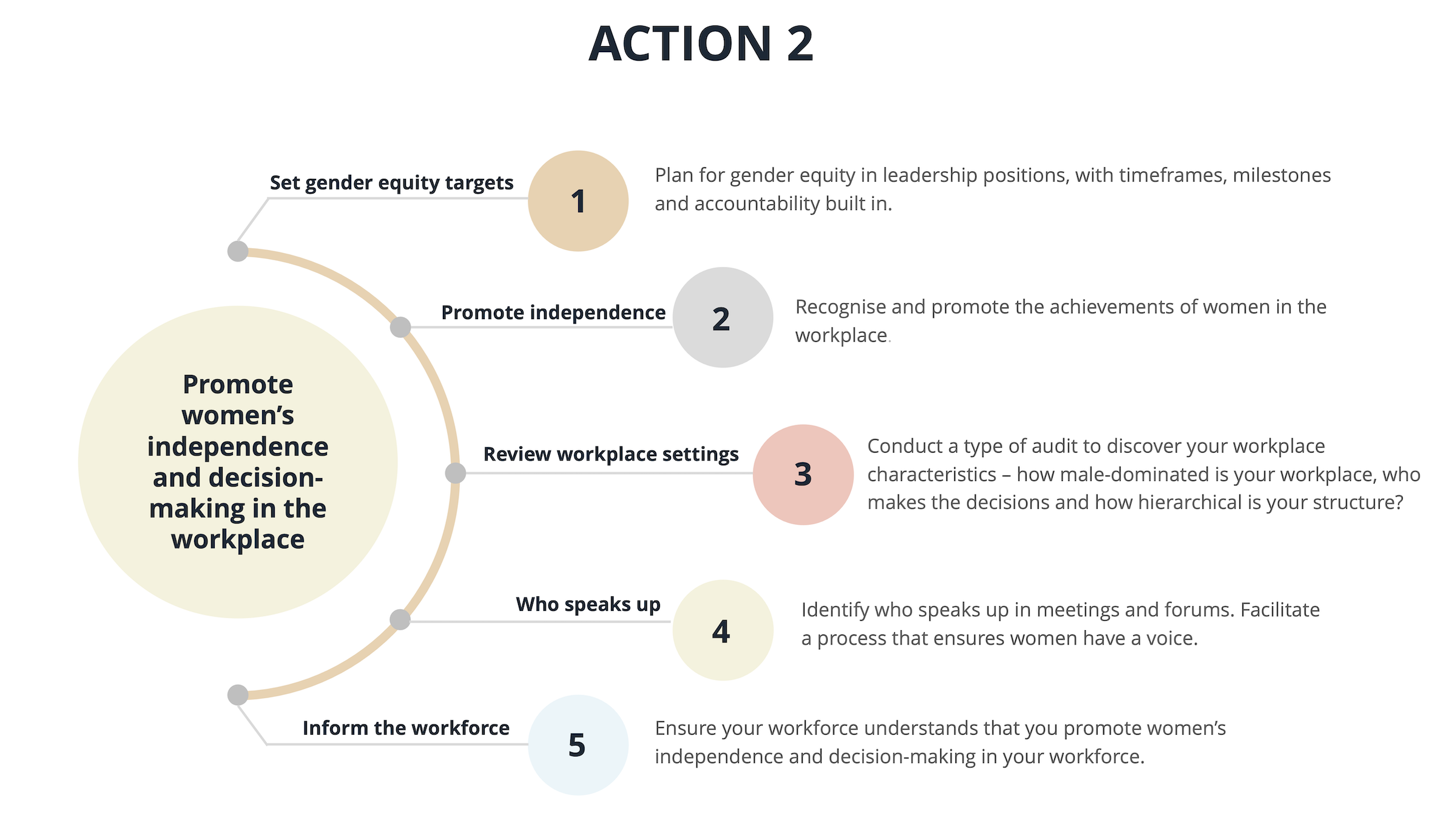

Driver 2: Men's control of decision making in public and private life

The way in which power is distributed between men and women in the private and public spheres, including in the workplace, is an important dimension of gender inequality. Evidence has suggested that men’s dominance of decision-making in public and private life, and limits to women’s autonomy, may contribute to sexual harassment against women for several reasons, including:

- Women’s lower status may serve a symbolic function that communicates that women have a lower social value and are less worthy of respectful treatment.

- Violence may be used and accepted as a mechanism for maintaining the dynamic of male dominance and female subordination, especially when male dominance is under threat.

- If women’s participation in formal decision-making and civic action is circumscribed, there is less opportunity for women to act collectively in the interests of preventing sexual harassment against women.

Click on the link below to consider what actions you can take to address driver 2.

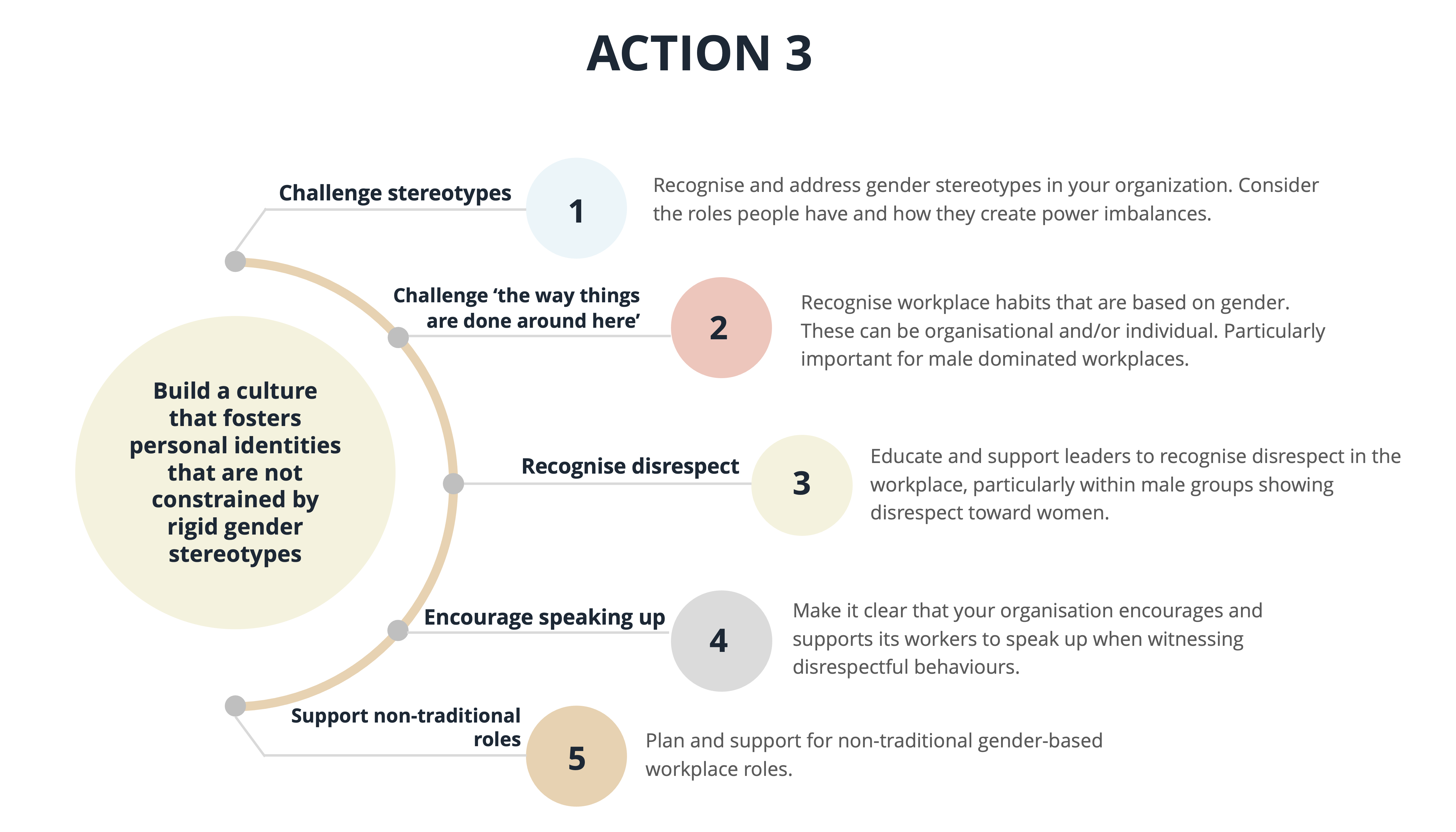

Driver 3: Rigid adherence to gender roles and stereotyped constructions of masculinity and femininity

A strong belief in stereotyped constructions of ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ and rigid distinctions between the roles of people are consistently associated with higher levels of sexual harassment against women. These stereotypes relate to the idea that people are ‘naturally’ suited to different tasks and responsibilities and have naturally distinctive personal characteristics.

This influences how people believe ‘proper’ or ‘real’ men and women should think, feel, and behave. Dominant forms of masculinity are associated with characteristics such as strength, independence, confidence, and aggression, while femininity is associated with sensitivity, passivity, dependence, and moral purity. Gender stereotypes affect the way in which roles and responsibilities are distributed between men and women in the family and in public life, including at work. Gender stereotypes contribute to gender segregation in the workforce with, for example, a far higher proportion of women than men in lower-paid ‘caring’ work such as childcare and aged care.

Click on the link below to consider what actions you can take to address driver 2.

Driver 4: Male peer relations that emphasises aggression and disrespect towards women

Male peer relations (including in a work context) that reinforce stereotypical and aggressive forms of masculinity are also associated with higher levels of sexual harassment against women, as they can create disrespect for, objectification of, or hostility towards women. Research has suggested that this may occur because:

- Violence, sexual harassment, and disrespect towards women are normalised through these peer relations.

- Men may more readily excuse their peers’ disrespectful behaviour towards women

- Men may be discouraged from taking a stand against this behaviour because they fear rejection by their peers.

Research has found that when men participate in sexist jokes and commentary, this ‘forms a type of in-group bonding and reinforces stereotypical or “traditional” masculine identities.’ When attitudes and behaviour that emphasise disrespect towards women, such as sexual harassment, become normalised within a workplace, women as well as men may stop questioning the behaviour. Negative male peer relations can contribute to an environment where workers and workplace leaders are unwilling to challenge disrespectful attitudes and behaviours for fear of exclusion or reprisal.

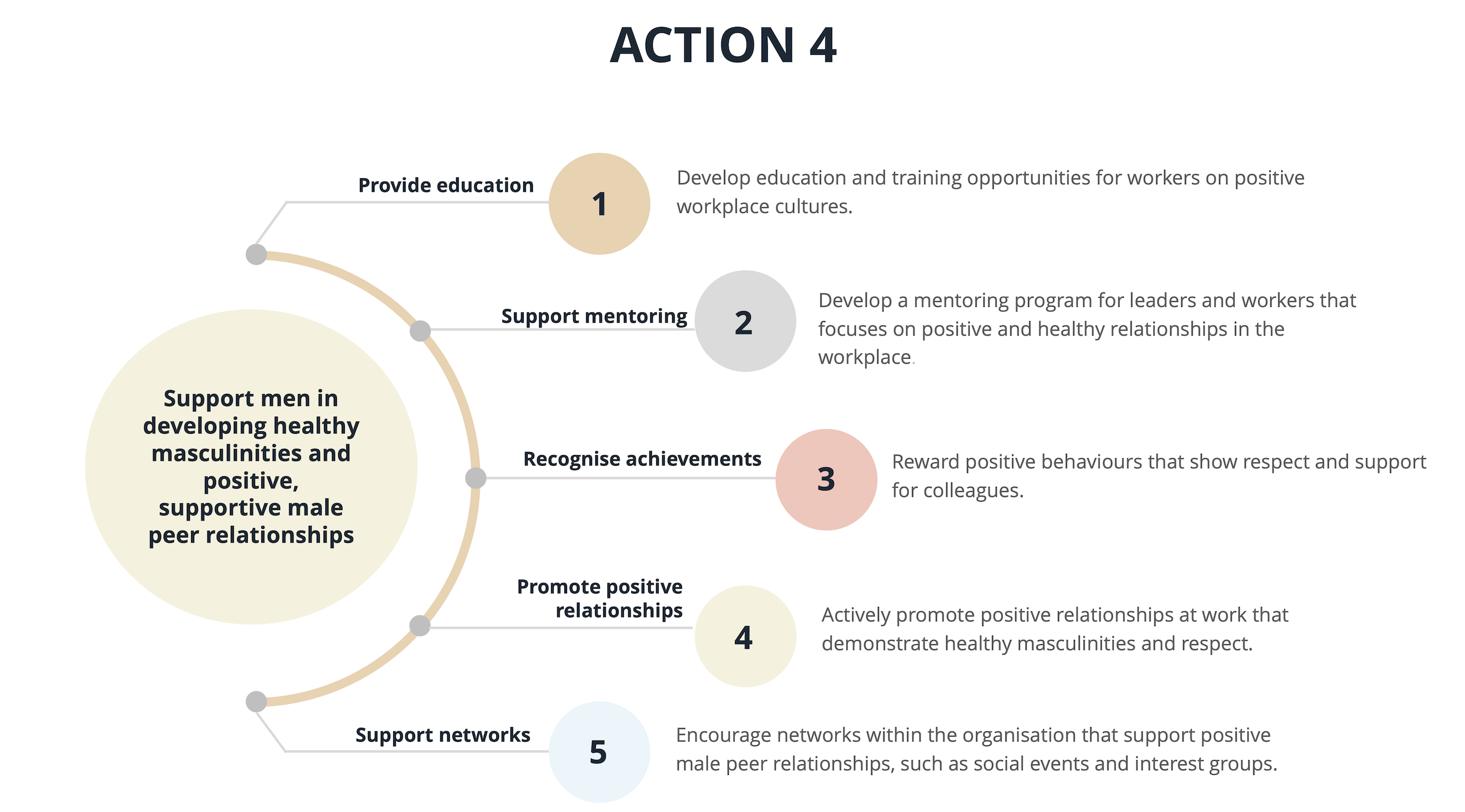

Click on the link below to consider what actions you can take to address driver 4.

You can download the slide deck of the gendered drivers of sexual harassment for your use in the sidebar on this page.